Reflection of 2025

What a crazy year it's been. For the first half of the year, I was still a student at what I (not humbly) consider the best university in the world: The University of Michigan.

Senior Spring at Michigan

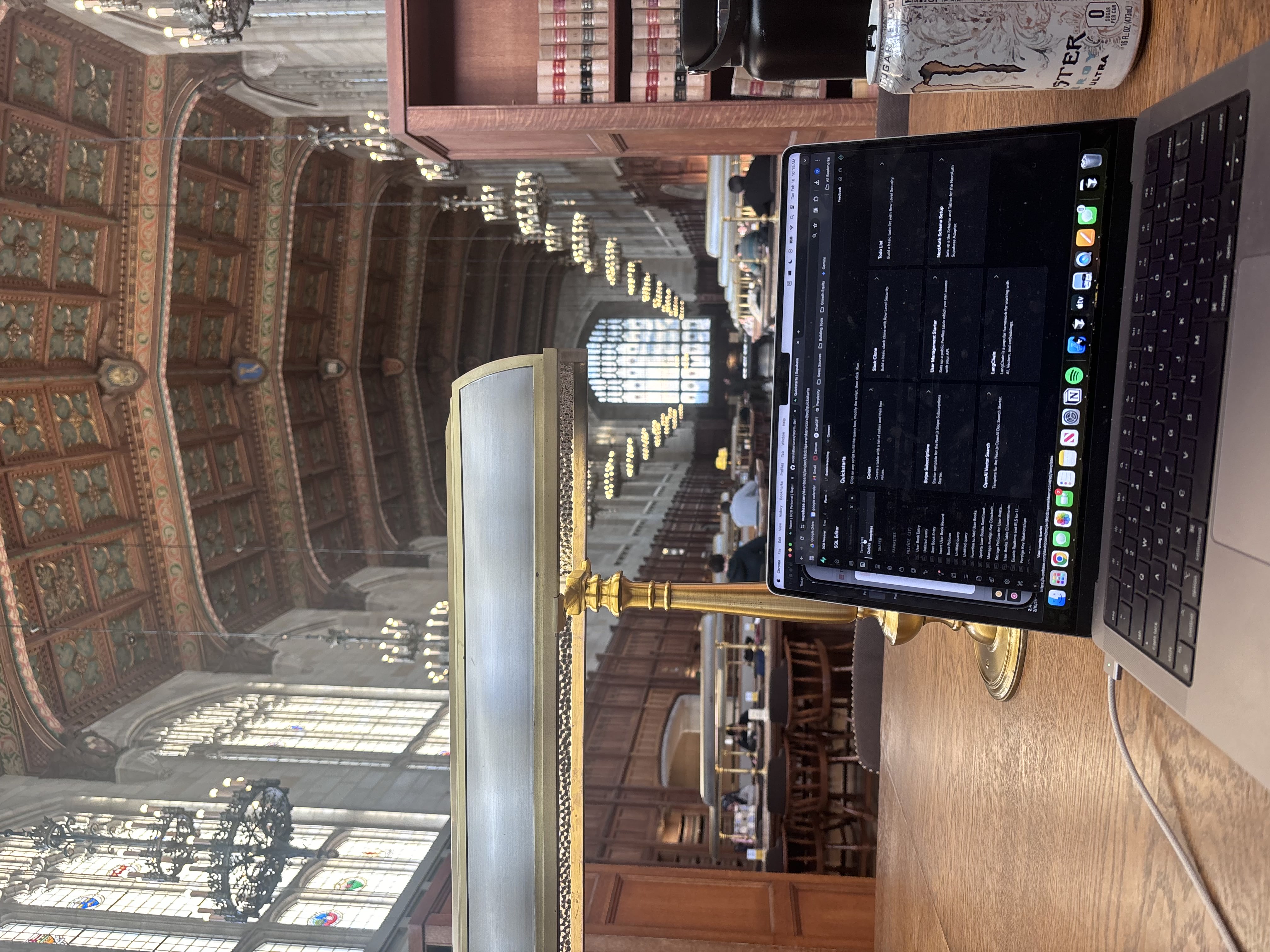

I lived with 11 of my closest friends. I had 200 friends (using this word lightly) within a 2-mile radius. I went out twice a week. I spent my days in class and in Law Library buried in my digital garden.

At the time, I was focused on trying to upskill myself. I had already landed a job as a Strategic Projects Lead at Scale AI, but recruiting had consumed much of my first semester. I wanted to take the time I had left on campus, time not yet owed to anyone else, and spend it intentionally.

I thought the best way to do this was to learn how to code and build deep relationships.

Learning How to Code

This was the most mentally taxing part of my day. Going from nothing to competent enough to build real things was hard.

The best analogy I have is learning to write. You start by learning the alphabet, isolated symbols that don't mean anything on their own. Then you learn words, but words are strange: "love" has an "O" in it, but it doesn't sound like the "O" you learned. The rules you memorized start breaking, and there's a bunch of exceptions necessitating that you relearn what an "O" really was in the first place. Then you learn sentences, trying to string them together into essays. Each layer builds on the last, but each layer also has its own logic that isn't obvious from the previous layer.

Coding is the same. You learn that a function takes an input and returns an output. Simple enough. But then you encounter something like the observer pattern, where objects notify other objects about state changes, and that's when my brain starts to hurt.

I learned through projects. First, I built a simple messaging app. All it had was proper authentication that logged a user into a page with a white background. Users could post messages. I deployed to a free Vercel domain and gave it to my friends who were out on a Thursday. It was fun to see my friends blow the chat app up, texting vulgar things to each other throughout the night. I created something out of thin air and my friends actually derived a night of utility from it. How cool! That is when I got hooked on building.

The second project was a personal portfolio optimizer. I baked in everything I had learned in my portfolio management class: diversification, rebalancing, optimizing for a given level of risk. My modest portfolio is up 27.6% over the past year, compared to a 16% rise in the S&P 500, so the exercise bore some utility here too.

Both of these projects were relatively simple, and I built every piece myself.

In late January, one of my good friends, Daniel Kates, took me out to coffee with an idea. I still don't know why he thought of me. I was a toddler just learning to code compared to some real heavy hitters on campus he knew well. He pitched me on the idea that there was no good book app. He wanted to build the Beli (a restaurant recommendation app that has replaced Yelp for our generation) for books.

I thought it was brilliant. I'm a book lover, but I struggle to reliably discover my next read. Goodreads compresses nearly every title between four and five stars because it's a subjective rating system. Everyone's "four stars" means something different. This idea, which we named Worm, uses a pairwise comparison algorithm that ranks books against each other. Instead of asking "how good is this book?", it asks "which of these two books is better?" The result is an objective ranking.

The deadline I set, April 2025, wasn't realistic if I kept learning the fundamentals. So I started using AI more and more to write code for me. I found I could move much faster. In four months, I built a functioning app which was accepted into the App Store. Instead of learning the granularities of code like efficiently managing memory through precise code optimizations, the skills I built during this phase were how to scaffold an agent to build software. I learned how to make sure the agent got the right context and how the agent could help me understand what we're trying to do. The skill I learned was how to arrive at clarity.

I had three levels of success in mind for Worm. The first was learning how to build an end-to-end app. I achieved that by getting it live on the App Store. The second was my friends finding real value in it. I achieved that too. There are 200 real users of the platform and 20 of my friends have rated ~30 books each. Every now and then I get a text from a friend that they loved a book they found from Worm. That makes me happy. The third level is Worm becoming the de facto place for people to rate books. As of now, I've failed at that. To build a high-quality app that is better than the next best in market (GoodReads) is harder to do than I thought.

A lesson in humility.

The jury is still out on whether the AI-assisted path will serve me better or worse in the long run. Today, I've forgotten a lot of basic syntax because I rely so heavily on Claude Code. I don't think in the granular way most software engineers are trained to think. I think in systems architecture, data flow and state. I think of myself as a conductor: I don't really play any of the instruments, but I know the sounds they produce and how to string them together.

There are obvious shortcomings to this approach. Certain error logs take me hours to debug whereas they'd take an experienced dev ten minutes. I'm not nearly as competent at catching where my code might fail. AI is a crutch. I'm implicitly betting that models will keep improving fast enough to make fewer mistakes. Where AI fails, I still have to learn on my own. My friend calls this lazy learning because you only learn what you must. I'm definitely a lazy learner. I spent most of my effort thinking in the arriving-at-clarity step. I use agents to execute once I have that clarity. The lazy learning happens when it can't execute for me.

I believe coding will become like writing. Most people can write a few paragraphs. Few people can write well. Everyone will be able to code something, but building something excellent will still be hard. Both great writing and coding leverage you. Leverage is the unfair advantage.

The most important skill I've learned through this process is persistence. Models get you 80% of the way on the first shot, but that remaining 20% takes a while to figure out. What you need is agency, the belief that anything is really at your fingertips if you keep pushing. That is why I'm so happy to be alive today. Everything truly is at your fingertips if you push hard enough. There has never been a better time to be alive. I hope I can help create a world where my kids say the same sentence and mean it just as much.

Build Deep Relationships

A friend to all is a friend to none. 200 friends is unrealistic. I realized I needed to double down on the people I really enjoyed spending time with. It's a rare luxury to have so many relationships within a 2-mile radius. I took advantage of that by seeing the people I cared for as often as I could.

I laughed so hard I couldn't breathe. I belted Dog Days Are Over with arms around my friends on the roof of my house watching the sunrise. I had those heart-to-heart conversations cuddled up together. I felt at home. I believe Michigan is the best university in the world for the people it attracts. Thank you to everyone for making it feel like home.

After graduating, I flew to Asia for a month with 15 of my best friends. You might think that's way too big, but it's actually the perfect size. At that scale, it's impossible to keep track of everyone. Your group each day is determined by when you wake up and what you want to do. During the day, I ranged from solo trips to groups of 4-5. If we wanted to party in the evenings, we'd all meet up. Traveling with medium-sized groups is often terrible because of coordination dependencies: making sure everyone's okay, waiting for stragglers. But once you get past a certain threshold, no one is looking out for anyone, and that's actually the best way to travel.

I ate a cobra's heart in Hanoi, bathed with elephants in Chiang Mai, cheered on the Muay Thai world championship at Rajadamnern in Bangkok, and played Nintendo 64 Mario Kart with Takashi-san, the bar owner and DJ of an 8-person bar in Kyoto. Most importantly, I made these memories with 15 of my closest friends.

Walking in the Dark: San Francisco, California

On August 1, I moved into a place I hadn't been within 1,000 miles of before: San Francisco, California.

When Scale AI originally made me an offer, they let me choose between New York and San Francisco. All my friends were moving to New York. My family is in Connecticut. My girlfriend lives in New York. The easy choice was obvious.

But after talking to people in industry who had lived in both cities, it became clear: while New York has a great emerging tech scene and is a strong number two, SF is 10x better. If my career truly came first, then I needed to be at the epicenter of all things AI. I had to move to where the action was happening, where people are thinking about and building with the tools at the forefront. I moved away from my family, my girlfriend, and the vast majority of my friends.

It was the right decision.

But I didn't feel that way at first. I felt all the things that are hard for me to admit. I felt alone. I felt scared. The harshness of reality was starting to set in.

On July 16, two weeks before I was supposed to move and three weeks before I was supposed to start, Scale AI rescinded my offer via email. In fact, they dropped our entire 28-person cohort. A few hours later, an HR person offered to take a call with me. When I tried probing for any explanation, he said he wasn't allowed to answer. What's the point of calling someone if you can't tell them anything?

By the time I moved to SF, I was still in the midst of the job hunt, in a city where I knew almost no one.

It was stressful. I remember sitting in a cafe the day my dad was flying back home after helping me move in. I didn't know what I was feeling, just a wave building over me. The wave crashed; I broke down crying in front of my dad for the first time in my life. My dad broke down crying too.

I wanted to leave this out because I'm embarrassed by it, but I'm owning it because life is scary when you're first starting out.

Everyone experiences this in one way or another. We're all just lost and figuring it out as we go. No one has it all figured out. People just don't like to admit it.

It's important to take that energy, the emotions coursing through you, and really channel it. I had to channel the emotion into productivity. But it was hard, because I had to think clearly about how to set myself up for success, and there was so much emotion clouding my judgment.

To gain clarity, I set up a framework for what I value most so I could evaluate opportunities honestly against that framework. For me, I cared about two things:

Learning (80%): The slope of learning mattered most to me. I split this into two parts: the people you work with and the type of work. The slope is highest when the five people you interact with most are high quality. They teach you the unknown unknowns. Talent tends to diffuse at larger organizations, so I focused on Seed to Series B companies. For the type of work, I wanted to learn durable skills that mapped to what I saw myself doing in the future, which is building my own company. I also wanted to be in-person. Learning happens at a much higher rate when you're in the foxhole together.

Status (20%): Status matters because it opens doors. Like it or not, people are more willing to meet you if you have credentials that say you're worth their time. Working at a known company and riding their tailwinds boosts your trajectory. High-status companies tend to have high talent density. People at these places tend to stay in the SF ecosystem and eventually proliferate to other companies within it that you can join, as scaling successful companies always eventually becomes a talent problem and talent tends to hire other talent they've worked with.

This was my framework. Everyone should come up with their own. Maybe you care most about money. Maybe it's a single skill like AI research. Doesn't matter—but having a durable framework takes the emotion out of decision-making.

Most of these learnings are hard-won knowledge that Dion Lim, my mentor, shook into me. I was lucky to have him. Dion is a superconnector whose life's purpose is helping his mentees and kids excel. He holds all of his mentees to the highest standards. He makes you think in terms of how the top 0.1% think. Most of all, he gives you the belief you need to have but don't have yet.

"You don't become confident by shouting affirmations in the mirror, but by having a stack of undeniable proof that you are who you say you are." — Alex Hormozi

When you've just graduated, you almost definitely have no proof whatsoever that you'll become what you dream of becoming. The gap is too big, and you start to see how steep the climb is. It's a competitive world, and maybe you can't do all that you set out to do. College was a bubble. I got to have bold dreams and do the fake work that made me feel good at life, able to accomplish whatever I set my mind to. The problem is, college is a weak approximation of the real world at best.

Dion helped me maintain belief when reality was telling me I wasn't who I said I was. Everyone needs a champion. Dion was mine. Thank you, Dion.

Dion introduced me to my first people in SF. One person I'm especially grateful for is Vi Tran, another mentor who has become a friend. We were supposed to meet for a 30-minute coffee chat. It turned into a 5-hour walk across San Francisco.

By the end of the walk, I felt like a local. I knew the fog was called Karl. I learned that the green and cherry-headed parrots became so plentiful because a local let his parrot fly free, and that parrot brought all his friends back to colonize SF. I mean, where's a better place to live?

There's a lesson here: always meet up in person. I'd go as far as to say don't take the meeting unless you can meet in person. Everything is still about relationships. It's hard to form real relationships over a screen. Virtual meetings feel transactional, and honestly, most of my virtual meetings were. An in-person meeting is the only way a 30-minute coffee chat turns into a 5-hour tour of the city.

Looking back, I'm so glad I was forced to move to SF jobless. If you don't have a job right out of college, just move to the city that's most known for the industry you want to succeed in. You have to get the wheel turning, and nothing catalyzes you like moving. There's a whole community of people who have been in the same position. They're more than willing to talk because they remember what it was like. It's scary, and we've all been there to varying degrees. I know I would take a meeting with anyone that reached out like this.

I got rejected from a bunch of jobs. Some companies I couldn't even get my foot in the door. Some I made it to a superday. Each rejection was a punch in the gut. Through this period, I learned the importance of optimism. I've always been an optimistic person, but my optimism started to waver for the first time in my life. I didn't know if I was cut out for it. My support system held me up. They were my optimism when I couldn't muster it myself. They knew light would come at the end of the tunnel. I just had to keep walking.

This is why relationships are the most important thing in my life. They're there when I'm in the dark, and I get to be there for them, in their dark moments and in their victories. Relationships are what make life special.

I ended up at a startup called Arphie, an AI-powered platform that helps companies respond to RFPs and security questionnaires. The founder, Dean Shu, was previously Chief of Staff to Alexandr Wang at Scale AI, as well as at Insight Partners, so he took my cold LinkedIn DM. It turned out they were looking for someone to help build their GTM engine. I loved the learning opportunity, really respected the team after a work trial, and turned down an offer for more than 2x the salary to join.

Why? The framework held. Learning slope mattered most. A team of 7 people, in-person, building something real.

Today

Building Leverage with AI

At Arphie, I'm always thinking about how to get something done as quickly as possible in a durable way. That's what led me to build systems that automate parts of the GTM workflow.

I own from first interaction with potential customers to upselling customers. Depending on the size of this company, this used to be owned by hundreds if not thousands of people. I am attempting to do all the work myself.

How am I able to do all of this work? I'm the conductor controlling various agents. Realistically, I am the head of a string puppet show right now. I can control only so many agents and those agents need a lot of guidance, but I am building my setup toward a world controlling a swarm of agents that can do entire job functions. It's a skill to learn how to control your agents. To do this, it's best to think in systems.

Take sales. The goal is to identify and sell your solution to the right people. To break down this workflow, you need to be able to determine who your ideal customer is given a company. Given an ideal customer, you need to determine who the key decision maker is. Given a key decision maker, you need to determine the right experience that will get them to buy your solution. This workflow is a system. One variable that matters a lot is the ideal customer. I spent a good chunk of time developing scripts to find verified customer lists of our competitors in the market.

I built a personal operating system using Claude's Agent SDK and Skills to let agents run these workflows autonomously, using the scripts I built as tools. The layers stack: I can take any company or list of companies and move through the entire workflow from identification to outreach.

Because we're a team of 7, we all share a small office space. We're constantly sharing context about what we're working on and doing post-mortems on problems. All of my work is complete whitespace. No one hands me tasks. I have to figure out what the highest-leverage thing is and then go execute. I spend about 60% of my time identifying customers of legacy competitors, 20% on answer engine optimization, and 10% of my time dealing with customers (whether scoping out issues or onboarding them onto the platform). The only time I receive work is when a customer pings us with a problem.

On the side, I spend 10% of my time learning the codebase and shipping small PRs to learn our codebase. Our codebase is a great artifact for me to learn from because our CTO was previously head of core infrastructure at Palantir. He cares deeply about high-quality code. When I was building Worm, it was all about shipping as fast as possible to get to a working product. Now, it's about shipping something my CTO approves without revisions. I'm learning things I never thought would matter, like type safety with Zod.

What's wild is being on the ground floor of this AI wave. The friction between having an idea and building a solution has collapsed. One person can now build what used to require a 100-person team 20 years ago. A 10-person team can build something previously impossible to do 10 years ago. It's ridiculous how much leverage a single person can generate.

I'm using tools that were released months ago. Claude Code has existed for less than a year, but I feel like I've been using it for two. The ecosystem is building on itself so fast. Everyone is using AI to build AI tools that other people use to build their AI tool. It takes a village, and that's exactly what's happening in SF.

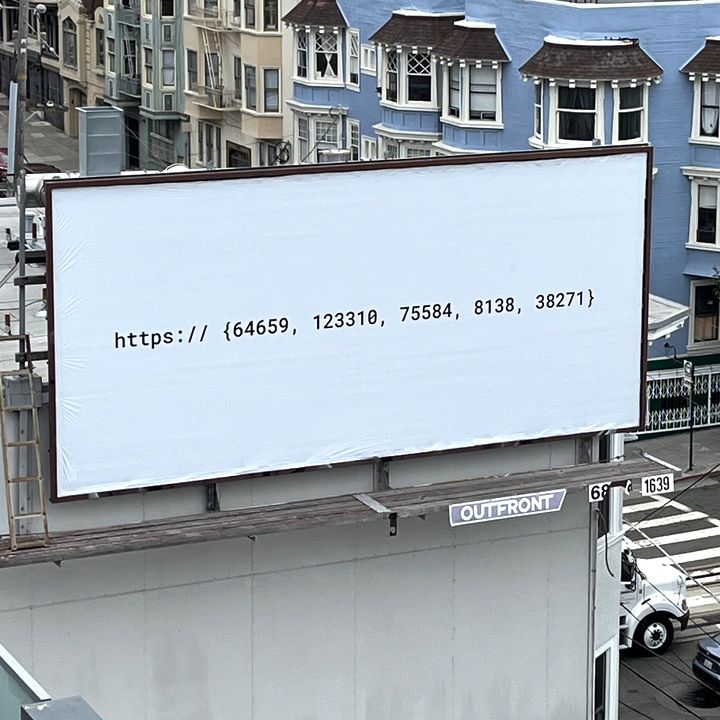

You feel it walking around San Francisco. AI ads are everywhere. There's a talent war and a product war happening simultaneously. Listen Labs ran an ad that was literally just a puzzle.

Another ad paints this dystopian picture of work being AI's life.

Everyone is trying to capture the attention of early adopters who will pay to experiment with anything that might give them leverage.

80% of the tools I'm using daily didn't exist two years ago. I'm excited to see what I'll be using in five years.

Social

During senior year, my strategy was to build deep relationships. But moving to a new city means opening the network again. I like to say I'm in the market for friends.

If you're moving to a new city, even if you have a great group of friends coming with you, adopt a mindset of meeting everyone. I texted all my friends to ask who they knew in San Francisco. One close friend introduced me to a friend of his friend. I met amazing people this way, including Trip Gorman through Barry Sabin.

Another approach is attaching yourself to someone who's already established. I was distant friends with Shrey Pandya in college. Since moving to SF, we've become close. He's introduced me to all his closest friends, and it's been amazing to integrate with a new group of people who are all interested in the same things.

It's funny how the things that made me weird in one group make me normal in a different group. My college friends would yawn when I started nerding out about my bottoms-up learning approach. This group leans in.

What I'd Tell My Past Self

Steve Jobs said it best: you can only connect the dots looking backwards. Looking forward, you just have to trust that they'll connect somehow.

The best thing to do, in my opinion, is to narrow down your options by eliminating what you don't want to do. You start college being able to go 360 degrees. The point of college is to narrow that down to 90 degrees, to figure out the general direction you want to head in.

To narrow things down, you have to explore. You have to learn what the different paths are actually like, not just what people tell you they're like. Don't follow what others say or where the status is. That won't serve you well long-term.

Try to notice what you're naturally drawn to. Do you think about it in the shower in the morning? If not, keep exploring. A strong proxy is if you are naturally good at it compared to your peers. If you're good at something, you tend to like it.

This isn't "follow your passion." That's bullshit because no one knows what their passion is. It's "eliminate what's not your passion."

Who I Am Now

I'm a person who got slapped in the face by the real world. I experienced thrash, but I'm getting my footing under me now. For everyone who says college is the best years of your life, I think you're wrong. Life is just different.

In some ways, your 20s are way better. Financial freedom. The feeling of actually adding to the world. I've found 1,000 verified customers of our legacy competitors. At our average deal size, that's $50 million in potential revenue. I plan to win over 5% in the next year. That's real value I never got to create in college.

In some ways, it's harder. You can't dive into any random learning rabbit hole; it needs to be at least adjacent to something productive. You're not surrounded by all of your closest relationships anymore.

I take a protected day off every Saturday. I've bodysurfed the waves at Ocean Beach, soaked in the fall sun at Stinson, biked across the Golden Gate Bridge, stared up at redwoods in Muir Woods, and watched the most beautiful sunset of my life at Point Reyes.

This year has been when my wings started to support myself. As someone who loves nothing more than freedom, that's all I can ask for.

I am building. I am living. It's been a roller coaster, but 2025 has been great to me. There's a lot of room to improve David Burton. Luckily, I have mentors that give me feedback, so I can continue chasing the best version of me. One improvement area is better discernment. My goal is to publish articles bi-weekly to grow this muscle.

I'm excited to tackle 2026 with as much energy as I brought to 2025.